Planning Meals, Weekly Shop, Alternative Constructors Using Class Methods

You can have more than one way of creating objects • alternative constructors using class methods

I’m sure we’re not the only family with this problem: deciding what meals to cook throughout the week. There seems to be just one dish that everyone loves, but we can hardly eat the same dish every day.

So we came up with a system, and I’m writing a Python program to implement it. We keep a list of meals we try out. Each family member assigns a score to each meal. Every Saturday, before we go to the supermarket for the weekly shop, we plan which meals we’ll cook on each day of the week. It’s not based solely on the preference ratings, of course, since my wife and I have the final say to ensure a good balance. Finally, the program provides us with the shopping list with the ingredients we need for all the week’s meals.

I know, we’ve reinvented the wheel. There are countless apps that do this. But the fun is in writing your own code to do exactly what you want.

I want to keep this article focussed on just one thing: alternative constructors using class methods. Therefore, I won’t go through the whole code in this post. Perhaps I’ll write about the full project in a future article.

So, here’s what you need to know to get our discussion started.

Do you learn best from one-to-one sessions? The Python Coding Place offers one-to-one lessons on Zoom. Try them out, we bet you’ll love them. Find out more about one-to-one private sessions.

Setting the Scene • Outlining the Meal and WeeklyMealPlanner Classes

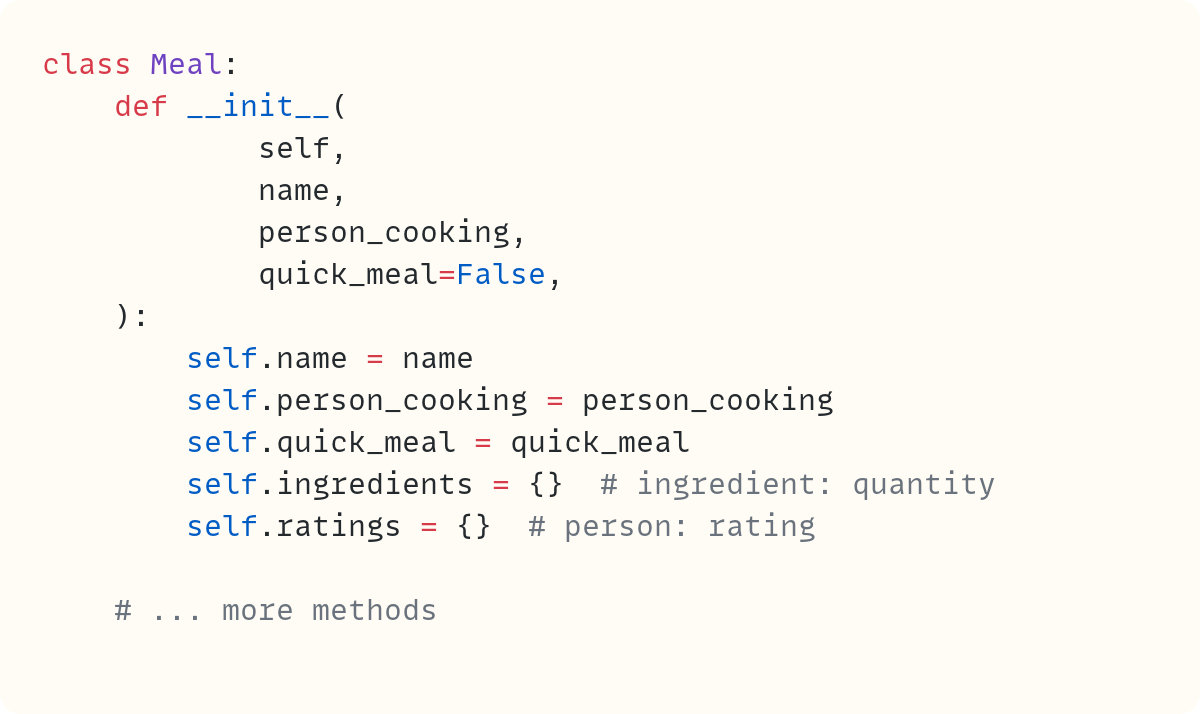

Let me outline two of the classes in my code. The first is the Meal class. This class – you guessed it – deals with each meal. Here’s the class’s .__init__() method:

The meal has a name so we can easily refer to it, so there’s a .name data attribute. And the meals I cook are different from the meals my wife cooks, which is why there’s a .person_cooking data attribute. This matters as on some days of the week, only one of us is available to prepare dinner, so this attribute becomes relevant!

There are also days when we have busy afternoons and evenings with children’s activities, so we need to cook a quick meal. The .quick_meal data attribute is a Boolean flag to help with planning for these hectic days.

Then there’s the .ingredients data attribute. You don’t need me to explain this one. And since each family member rates each meal, there’s a .ratings dictionary to keep track of the scores.

The class has more methods, such as add_ingredient(), remove_ingredient(), add_rating(), and more. There’s also code to save to and load from CSV and JSON files. But these are not necessary for today’s article, so I’ll leave them out.

There’s also a WeeklyMealPlanner class:

The ._meals data attribute is a dictionary with the days of the week as keys and Meal instances as values. It’s defined as a non-public attribute to be used with the read-only property .meals. The .meals property returns a shallow copy of the ._meals dictionary. This makes it safer as it’s harder for a user to make changes directly to this dictionary. The dictionary is modified only through methods within WeeklyMealPlanner. I’ve omitted the rest of the methods in this class as they’re not needed for this article.

You can read more about properties in Python in this article: The Properties of Python’s ‘property’

So, each time we try a new dish, we create a Meal object, and each family member rates it. This meal then goes into our collection of meals to choose from each week. On Saturday, we choose the meals we want for the week, put them in a WeeklyMealPlanner instance, and we’re almost ready to go…

At the Supermarket

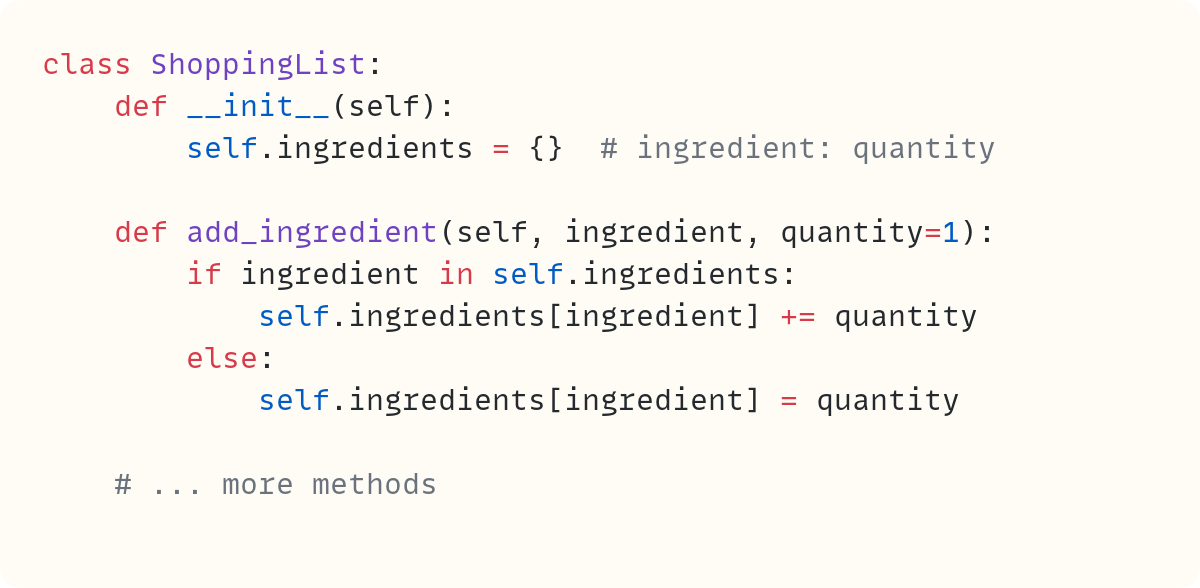

Well, we’re almost ready to go to the supermarket at this point. So, here’s another class:

A ShoppingList object has an .ingredients data attribute. This attribute is a dictionary. The keys are the ingredients, and the values are the quantities needed for each ingredient. I’m also showing the .add_ingredient() method, which I’ll need later on. So, you can create an instance of ShoppingList in the usual way:

Then, you can add ingredients as needed. But this is annoying for us on a Saturday. Here’s why…

Do you want to master Python one article at a time? Then don’t miss out on the article in The Club which are exclusive to premium subscribers here on The Python Coding Stack

Alternative Constructor

Before describing our Saturday problems, let’s briefly revisit what happens when you create an instance of a class. When you place parentheses after the class name, Python does two things: it creates a blank new object, and it initialises it. The creation of the new object almost always happens “behind the scenes”. The .__new__() method creates a new object, but you rarely need to override it. And the .__init__() method performs the object’s initialisation.

You can only have one .__init__() special method in a class. Does this mean there’s only one way to create an instance of a class?

Not quite, no. Although there’s no way to define more .__init__() methods, there are ways to create instances through different routes. The @singledispatchmethod decorator is a useful tool, but one I’ll discuss in a future post. Today, I want to talk about using class methods as alternative constructors.

Back to a typical Saturday in our household. We just finished choosing the seven dinners we plan to have this coming week, and we created a WeeklyMealPlanner instance. So we should now create a ShoppingList instance using ShoppingList() and then go through all the meals we chose, entering their ingredients.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could just create a ShoppingList instance directly from the WeeklyMealPlanner instance? But that would require a different way to create an instance of ShoppingList.

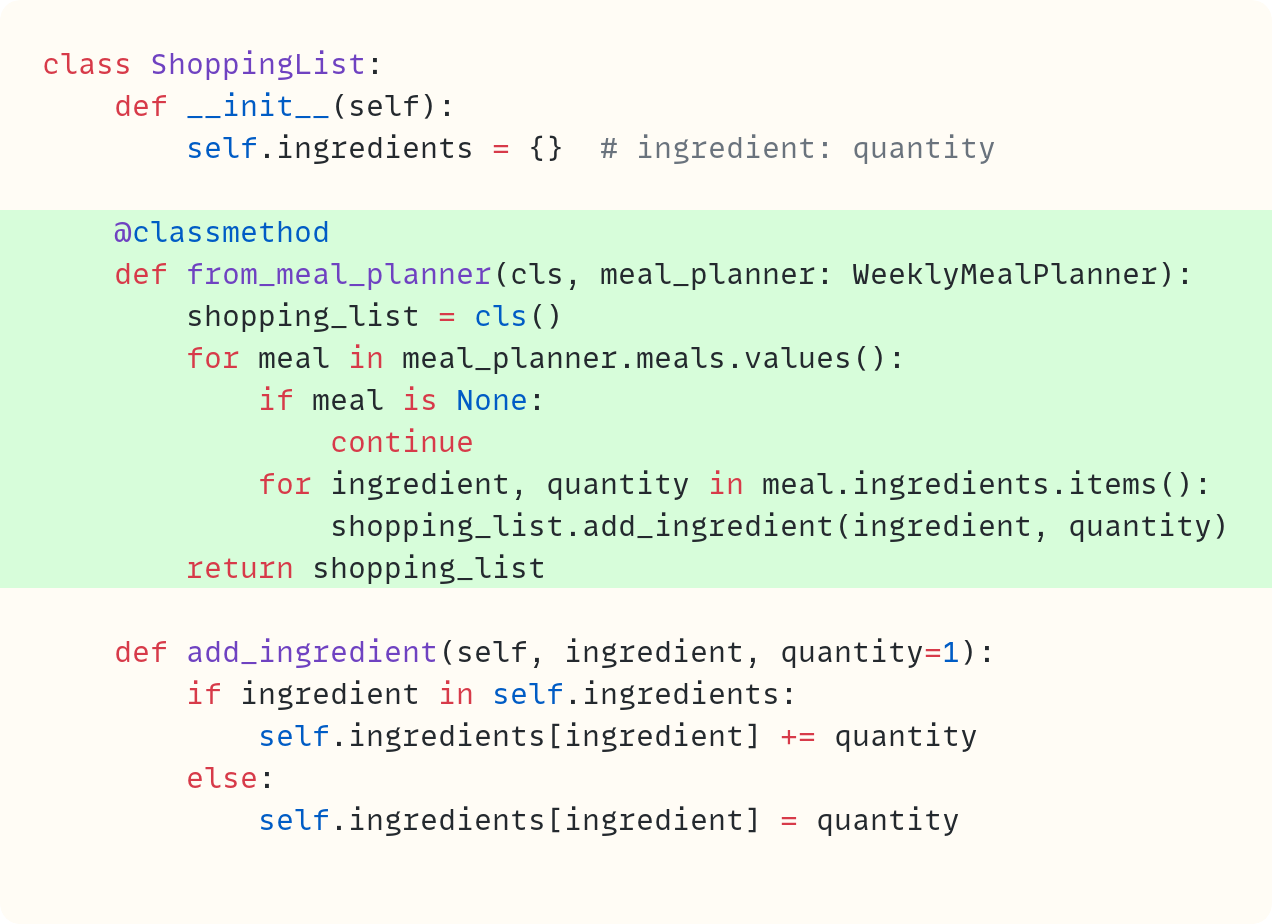

Let’s define an alternative constructor, then:

There’s a new method called .from_meal_planner(). However, this is not an instance method. It doesn’t belong to an instance of the class. Instead, it belongs to the class directly. The @classmethod decorator tells Python to treat this method as a class method. Note that the first parameter in this method is not self, as with the usual (instance) methods. Instead, you use cls, which is the parameter name used by convention to refer to the class.

Whereas self in an instance method represents the instance of a class, cls represents the class directly. So, unlike instance methods, class methods don’t have access to the instance. Therefore, class methods don’t have access to instance attributes.

The first line of this method creates an instance of the class. Look at the expression cls(), which comes after the = operator. Recall that cls refers to the class. So, cls is the same as ShoppingList in this example. But adding parentheses after the class creates an instance. You assign this new instance to the local variable shopping_list. You use cls rather than ShoppingList to make the class more robust in case you choose to subclass it later.

Fast-forward to the end of this class method, and you’ll see that the method returns this new instance, shopping_list. However, it makes changes to the instance before returning it. The method fetches all the ingredients from each meal in the WeeklyMealPlanner instance and populates the .ingredients data attribute in the new ShoppingList instance.

In summary, the class method doesn’t have access to an instance through the self parameter. But since it has access to the class, the method uses the class to create a new instance and initialise it, adding steps to the standard .__init__() method.

Therefore, this class method creates and returns an instance of ShoppingList with its .ingredients data attribute populated with the ingredients you need for all the meals in the week.

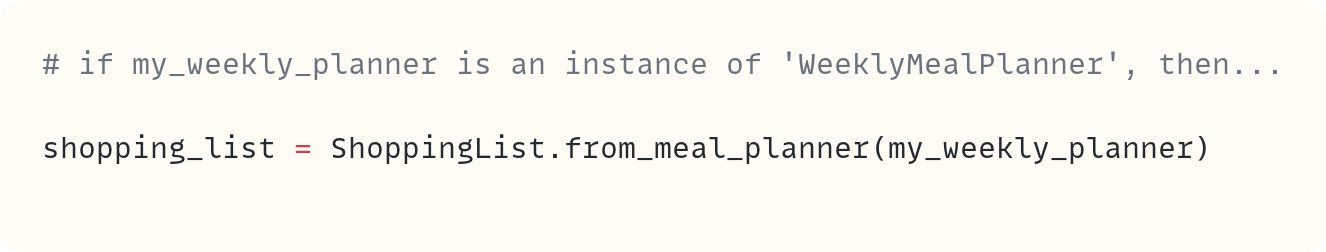

You now have an alternative way of creating an instance of ShoppingList:

This class now has two ways to create instances. The standard one using ShoppingList() and the alternative one using ShoppingList.from_meal_planner(). It’s common for class methods used as alternative constructors to have names starting with from_*.

You can have as many alternative constructors as you need in a class.

Question: if it’s more useful to create a shopping list directly from the weekly meal planner, couldn’t you implement this logic directly in the .__init__() method? Yes, you could. But this would create a tight coupling between the two classes, ShoppingList and WeeklyMealPlanner. You can no longer use ShoppingList without an instance of WeeklyMealPlanner, and you can no longer easily create a blank ShoppingList instance.

Creating two constructors gives you the best of both worlds. ShoppingList is still flexible enough so you can use it as a standalone class or in conjunction with other classes in other projects. But you also have access to the alternative constructor ShoppingList.from_meal_planner() when you need it.

Alternative Constructors in the Wild

You may have already seen and used alternative constructors, perhaps without noticing.

Let’s consider dictionaries. The standard constructor is dict() – the name of the class followed by parentheses. As it happens, you have several options when using dict() – you can pass a mapping, or an iterable of pairs, or **kwargs. You can read more about these alternatives in this article: dict() is More Versatile Than You May Think.

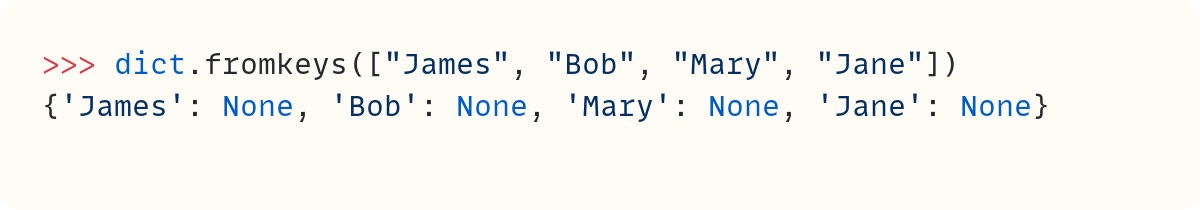

But there’s another alternative constructor that doesn’t use the standard constructor dict() but still creates a dictionary. This is dict.fromkeys():

You can have a look at help(dict.fromkeys). You’ll see the documentation text refer to this method as a class method, just like the ShoppingList.from_meal_planner() class method you defined earlier.

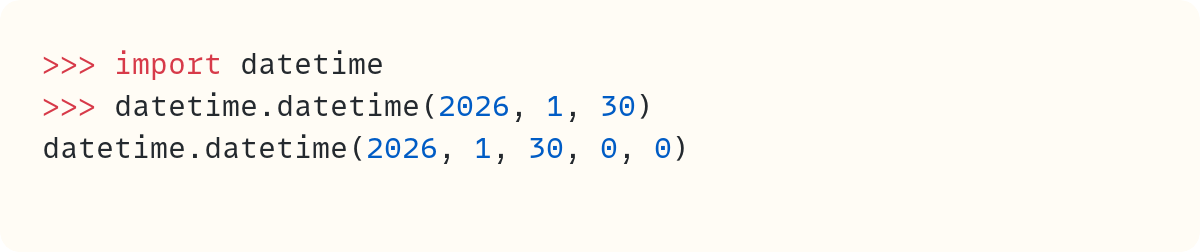

And if you use the datetime module, you most certainly have used alternative constructors using class methods. The standard constructor when creating a datetime.datetime instance is the following:

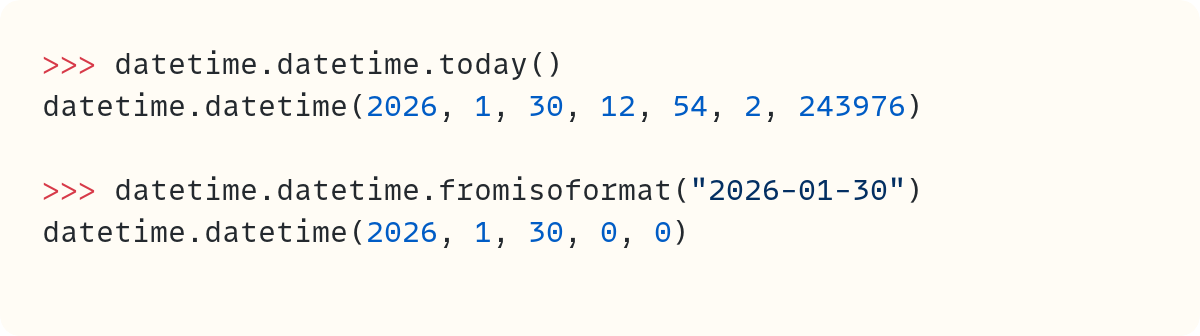

However, there are several class methods you can use as alternative constructors:

Have a look at other datetime.datetime methods starting with from_.

Your call…

The Python Coding Place offers something for everyone:

• a super-personalised one-to-one 6-month mentoring option

$ 4,750

• individual one-to-one sessions

$ 125

• a self-led route with access to 60+ hrs of exceptional video courses and a support forum

$ 400

Final Words

Python restricts you to defining only one .__init__() method. But there are still ways for you to create instances of a class through different routes. Class methods are a common way of creating alternative constructors for a class. You call them directly through the class and not through an instance of the class – ShoppingList.from_meal_planner(). The class method then creates an instance, modifies it as needed, and finally returns the customised instance.

Now, let me see what’s on tonight’s meal planner and, more importantly, whether it’s my turn to cook.

Code in this article uses Python 3.14

The code images used in this article are created using Snappify. [Affiliate link]

Join The Club, the exclusive area for paid subscribers for more Python posts, videos, a members’ forum, and more.

You can also support this publication by making a one-off contribution of any amount you wish.

For more Python resources, you can also visit Real Python—you may even stumble on one of my own articles or courses there!

Also, are you interested in technical writing? You’d like to make your own writing more narrative, more engaging, more memorable? Have a look at Breaking the Rules.

And you can find out more about me at stephengruppetta.com

Further reading related to this article’s topic:

Appendix: Code Blocks

Code Block #1

class Meal:

def __init__(

self,

name,

person_cooking,

quick_meal=False,

):

self.name = name

self.person_cooking = person_cooking

self.quick_meal = quick_meal

self.ingredients = {} # ingredient: quantity

self.ratings = {} # person: rating

# ... more methods

Code Block #2

class WeeklyMealPlanner:

def __init__(self):

self._meals = {} # day: Meal

@property

def meals(self):

return dict(self._meals)

# ... more methods

Code Block #3

class ShoppingList:

def __init__(self):

self.ingredients = {} # ingredient: quantity

def add_ingredient(self, ingredient, quantity=1):

if ingredient in self.ingredients:

self.ingredients[ingredient] += quantity

else:

self.ingredients[ingredient] = quantity

# ... more methods

Code Block #4

ShoppingList()

Code Block #5

class ShoppingList:

def __init__(self):

self.ingredients = {} # ingredient: quantity

@classmethod

def from_meal_planner(cls, meal_planner: WeeklyMealPlanner):

shopping_list = cls()

for meal in meal_planner.meals.values():

if meal is None:

continue

for ingredient, quantity in meal.ingredients.items():

shopping_list.add_ingredient(ingredient, quantity)

return shopping_list

def add_ingredient(self, ingredient, quantity=1):

if ingredient in self.ingredients:

self.ingredients[ingredient] += quantity

else:

self.ingredients[ingredient] = quantity

Code Block #6

# if my_weekly_planner is an instance of 'WeeklyMealPlanner', then...

shopping_list = ShoppingList.from_meal_planner(my_weekly_planner)

Code Block #7

dict.fromkeys(["James", "Bob", "Mary", "Jane"])

# {'James': None, 'Bob': None, 'Mary': None, 'Jane': None}

Code Block #8

import datetime

datetime.datetime(2026, 1, 30)

# datetime.datetime(2026, 1, 30, 0, 0)

Code Block #9

datetime.datetime.today()

# datetime.datetime(2026, 1, 30, 12, 54, 2, 243976)

datetime.datetime.fromisoformat("2026-01-30")

# datetime.datetime(2026, 1, 30, 0, 0)

For more Python resources, you can also visit Real Python—you may even stumble on one of my own articles or courses there!

Also, are you interested in technical writing? You’d like to make your own writing more narrative, more engaging, more memorable? Have a look at Breaking the Rules.

And you can find out more about me at stephengruppetta.com